Interactivity & Multimedia in Learning

TEXT

When designing the textual presentation of information, a common “best practice” is to use a mix of Serif and Sans Serif typefaces to denote content hierarchy. Also, the text can use different point sizes for headings and major parts of the copy. To improve readability, consider having the copy left-justified with a ragged right margin. An effective use of type styles (italics, bold, underline) can be used to emphasize key terms and concepts. The text designer can also make effective use of kerning. “Kerning,” as explained by Lupton, 2010, pg. 102), refers to adjusting the spacing between letters: “Some letter combinations look awkward without special spacing considerations. Gaps occur, for example, around letters whose forms angle outward or frame an open space (e.g., W, &, V, T).”

Attention also needs to be given to appropriate line length — around 70 characters — again, to improve readability. In addition, the copy is more readable when the designer uses a good contrast between the text and the background, such as a strong, black-colored, Serif font on a white background. The use of “leading” can also affect readability by ensuring the spacing between lines is neither too crowded nor too open. The leading proportions allow the text to appear as part of an “overall visual shape and texture” rather than lines of type appearing as “independent graphic elements” (Lupton, 2010, pg. 108).

AUDIO & VIDEO

Research shows that there are different channels in the brain for processing visual and auditory information. Therefore, using audio as a supplement to printed material “allows us to off-load processing of words from the visual channel to the auditory channel, thereby freeing more capacity for processing graphics in the visual channel” (Clark & Mayer, 2016, pg. 116). Of particular concern to the instructional designer is that extraneous part of the load — the part that has nothing to do with the complexity of the material – because it can be affected by instructional interventions (van Merriënboer & Sweller, 2005, pg. 150). One important way to help manage the student’s extraneous cognitive load is by making appropriate use of the communication tools, such as text, sound, and graphics. (Clark, Nguyen, Sweller, 2006, pg. 43). Below is an example of a narrated screencast that makes use of audio and video.

AUDIO ONLY

Stand-alone audio files can also be a helpful tool. Careful attention needs to be paid to the environment where the audio is recorded. A quiet location with minimal background noise (appliances, barking dogs, noisy co-workers) and also good acoustics (carpet, soft window coverings — furnishings to minimize any echo effect). A good quality podcast headset with earpiece and microphone are worth the investment. Below is an example of a brief MP3 file.

GRAPHICS

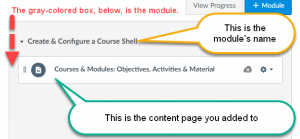

Annotated Screenshot

Often, a simple graphic can explain a multi-step process or clarify what is being discussed. The use of graphics should be intentional and serve a purpose. Here is a graphic that annotates a screenshot to explain the function of each element on the screen.

SCREEN-BASED INTERACTIVITIES

Finally, providing learners with an opportunity to engage and interact with the material can help keep them focused and interested. Below are examples of some “interactivities” that allow the user to click-through and engage with the information.

Overview of Major College Funding Streams

Creating an Online Course in the Canvas LMS

Personal Wrongs or “Torts” Against a Person

Structure of Arizona Courts

References

Clark, R.C. & Mayer, R.C. (2016). e-Learning and the science of instruction. 4th ed. Wiley

Clark, R.C., Nguyen, F. & Sweller, J. (2006). Efficiency in Learning: Evidence-based guidelines to manage cognitive load. San Francisco: Pfieffer

Lupton, E. (2010). Thinking with type: A critical guide for designers, writers, editors, & students. 2nd ed. Princeton Architectural Press: New York.

van Merriënboer, J. & Sweller, J. (2005). Cognitive load theory and complex learning: Recent developments and future directions. Educational Psychology Review, 17(2), 147-177. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10648-005-3951-0